This study uses the Drosophila genetic model system to selectively abolish dendrites from a subset of identified wing muscle motoneurons that have well-described and stereotyped dendritic morphologies ( 13) and firing patterns during flight ( 14) and courtship song ( 15, 16). Trying to understand dendrite function poses major technical challenges because it requires selective manipulation of dendritic structure without disturbing other properties of the affected neuron, followed by quantitative analysis of neuronal function and the resulting behavioral consequences. However, in many cases it remains unclear whether dendritic defects are the cause or the consequence of impaired brain function. In addition to functioning as passive receivers, dendrites may be equipped with output synapses ( 7) and active membrane currents ( 8), which add tremendous computational power to a single neuron ( 6, 9, 10).Īccordingly, dendritic abnormalities are highly consistent anatomical correlates of numerous brain disorders ( 11, 12), including autism spectrum disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, schizophrenia, Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, Rett syndrome, anxiety, and depression. The functions of dendrites are proposed to range from simply providing enough surface for synaptic input ( 3) to highly compartmentalized units of molecular signaling and information processing ( 4 – 6).

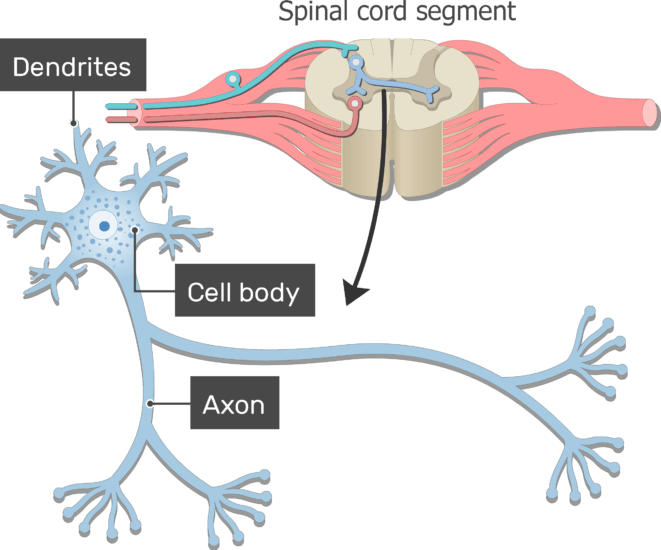

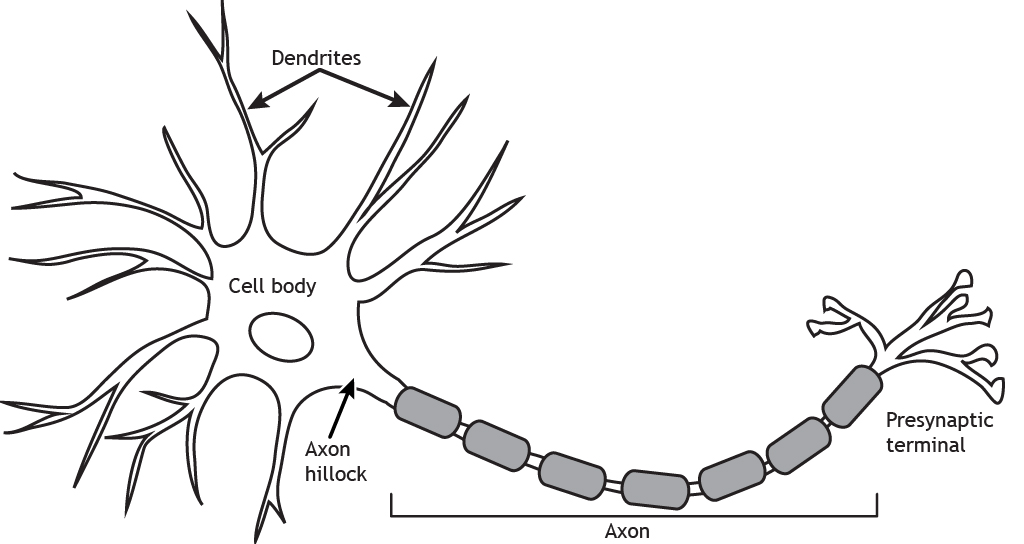

The estimated 100 billion neurons in the human brain ( 2) form approximately 100 trillion synapses onto a total of approximately 100,000 miles of dendritic cable. We speculate that the observed scaling of performance deficits with the degree of structural defect is consistent with gradual increases in intellectual disability during continuously advancing structural deficiencies in progressive neurological disorders.ĭendrites are structural ramifications of a neuron specialized for receiving and processing synaptic input ( 1). To our knowledge, our observations provide the first direct evidence that complex dendrite architecture is critically required for fine-tuning and adaptability within robust, evolutionarily constrained behavioral programs that are vital for mating success and survival. However, significant performance deficits in sophisticated motor behaviors, such as flight altitude control and switching between discrete courtship song elements, scale with the degree of dendritic defect. We find that these motoneuron dendrites are unexpectedly dispensable for synaptic targeting, qualitatively normal neuronal activity patterns during behavior, and basic behavioral performance. Here we probe dendritic function by using genetic tools to selectively abolish dendrites in identified Drosophila wing motoneurons without affecting other neuronal properties.

However, the precise consequences of dendritic structure defects for neuronal function and behavioral performance remain unknown. Defects in dendritic structure are highly consistent correlates of brain diseases. Dendrites are highly complex 3D structures that define neuronal morphology and connectivity and are the predominant sites for synaptic input.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)